There are many ways to tell a story and when it comes to repatriation, there are often multiple voices with different opinions. In the Yaqui case, there have been competing views on whether the objects should be returned. Some argued that they were stolen and should therefore be sent back. Others did not want the objects returned because it went against their ancestors' wishes to take back something that was once given as a gift.

Following a long process, it was decided that the ceremonial objects should be repatriated due to the fact that they were testimonies of an important period in Yaqui's history of deportation and life in exile.

The story of the Yaqui case is here presented in three films describing a repatriation case. The first film documents the process and relationship between Sweden and Mexico. The second film depicts the life of Yaquis today and their testimonies regarding this case. The third film describes a paralell research project designed to shed light on the multi- layered nature of this repatriation case.

In 1934, 24 ceremonial objects crossed the Atlantic Ocean and ended up in Sweden. In 2022 they returned home. The first film documents the process and the relationship between Sweden and Mexico.

Press T to turn on subtitles. You change the language of the subtitles by clicking the cogwheel and then clicking "undertexter".

Being yaqui means looking at the sun and being thankful for it. Teodoro Buitimea Flores, Teacher, Yaqui Nation.

The Yaqui case is one of many current repatriation cases in Sweden. In recent decades, European museums with so-called ethnographic collections have increasingly been met with requests from cultural communities with material cultural heritage located in museum collections around the world.

In repatriation dialouge, the terms repatriation, restitution and rematriation are commonly used. Restitution is the process by which cultural objects are returned to an individual or society. Repatriation is the process by which cultural goods are returned to a nation or state at the request of a government. The term rematriation refers to the proccess of bringing back cultural goods to one's motherland.

Press release from the National museums of World Culture May 5 2022

Formal demand from the Government of Mexico to the Museums of World Culture, February 19 2021 (PDF)

UHCHR - Repatriation request for the Yaqui Maaso Kova

The second film explores how silent museum objects can return to being yaqui objects filled with music, dance and celebration.

In 2019, members of Yaqui Nation visited Sweden with the task of studying the objects selected for a repatriation assessment. The group consisted of: Anabela Carlon Flores, lawyer and human rights specialist, Felix Espinoza Espinoza, violinist and cowboy, Teodoro Buitimea Flores, teacher and historian, and Fernando Jimenez Gutierrez, chapayeka and surveyor. They all hold important ritual and societal positions among the Yaquis in Sonora.

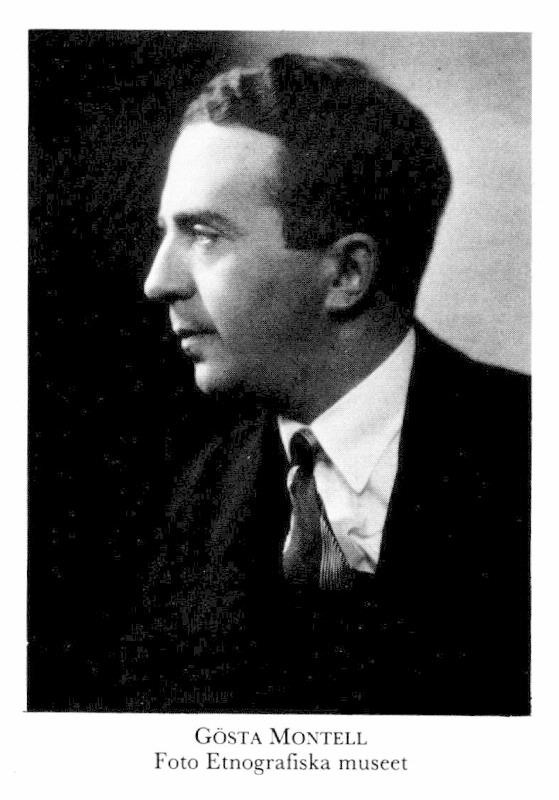

The group studied 24 ceremonial objects collected on December 4, 1934 in Tlaxcala during a lucto pajko, a ceremony dedicated to a person who had died the previous year. The collection was made by Gösta Montell and Sigvald Linné during the Second Swedish Mexico expedition, together with the Danish sisters Bodil Christensen and Helga Larsen.

All 24 objects in the collection were culturally identified during their visit. They were, for instance, able to establish that some objects came from Río Yaqui, others had been made in Tlaxcala. Fundamental in the work on the collection by the Yaqui delegation, was the conclusion that all these objects were witnesses to deportation during one of the most important and difficult periods in their history.

The ceremonial objects mainly represent four dances: Venado, Pascola, Matachin and Chapayeka.

Venado, the deer, is a sacred animal who symbolizes vitality and wellbeing. It is a wise and noble animal of unsurpassed purity. Venado is a cultural hero and for yaquis these elements are maintained during the dance performance.

The venado dance is a dramatization of the deer hunt, and the dancer representing the venado shows its stealthy movements and the need for protection from the hunt. The dance symbolizes man's relationship with nature and the divinity that dwells in the universe.

During the dance, the music and movements of deer dancer merges, the music becomes the breathing and lungs of the deer, revealing the animal´s changing states of mind.

The collection includes two sacred maaso koba, one is from Tlaxcala, the other from Yucatán. These ceremonial deer heads are used, for instance, during the venado dance (deer dance). A maaso koba used and blessed is a sacred living being, treated as a beloved relative. It is the Kolensia, the ceremonial society for the deer dance, who is responsible for the maaso koba, used for instance during the Venado dance.

According to the customs and traditions of the Yaqui, a consecrated and blessed maaso koba cannot be purchased, gifted or otherwise alienated to anyone other than a member of the Kolensia Society. An consecrated maaso koba can only be transferred to a younger person, educated by one of the elders to secure his place in the community.

This dance is performed during occasions such as Easter, Virgin Day or as in this case, during a so-called lucto pajko ceremony. All objects in this repatriation case were collected after such a ceremony was conducted. Pascola is also the title of a person with a prominent role both as a dancer, host, speaker and ritual clown.

During the dance, the pascola wears a belt with several metal bells, which makes a special sound when the dancer moves. A wooden rattle with small metal discs attached, is worn tucked under the dancer´s belt.

Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the pascola dancers regalias is a type of gaiters known as teneboim. They consists of strings of large silk butterfly cocoons filled with fine stones or sand collected from anthills, and are worn wrapped around both legs of the dancer. The sound that these make during the dance is similar to the sound of a rattlesnake, an animal culturally associated with rain and fertility.

In a Pascola´s regalia there are two more distinct elements: a wooden mask and la vela (light). When the pascola dances like a human, the mask is placed on the back of the head or over one ear, leaving the dancer's face revealed. When the dancer wants to represent an animal (or any other being), the mask covers the face as the dancer takes on the personality of that being.

The music is performed with harp and violin, two instruments that originally came with European settlers, along with the cane flute and leather drum, representing local traditions.

This is primarily a European dance introduced by the Catholic missionaries. The dance is dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the dancers, dressed in white with a crown on their heads, represent the tears of the Virgin Mary and the universe.

The Matachine dancers perform from Ash Wednesday to Easter Eve, but the dance can also be performed at funerals or at the end of the year as a reverence to someone who has made a special contribution to the community.

The dancers represent the soldiers of the Virgin Mary and, according to some legends, it was she who personally recruited and dressed them according to her wishes. Each part of a matachine's regalia somehow relates to her.

The red gourd, the three-pointed dance rod (palma) with tassels of colored feathers, and the crown with multicolored strips of paper – all of which are considered as "flowers" (sewa) in the yaqui world of thought. Flowers – and roses in particular – have of course long been associated with the Virgin Mary, but for many yaquis their meaning goes deeper.

Chapayeka are ritual clowns representing Judas. Chapayeka, which means long nose, fool around with the audience, and will even make obscene jokes with them. They wear masks that represent non-yaquis, animals, monsters, mythical figures, or nowadays various characters from television and movies.

The collection in question, includes a chapayeka mask; and according to tradition, these should be burned after they have been used during Easter. However, the mask found in the collection has no signs of having been used. It is quite possible that it was made as a regalia to be given as a gift to the Swedish expedition.

The final part looks at how the objects left their original time and place, and what it means for the Yaqui to have found their home again.

Yaqui Nation is located in the Río Yaqui Valley in the state of Sonora in northwestern Mexico. With the arrival of the Spaniards in the 1700s, Yaquis were christianized by jesuit missionaries, but still managed to preserve much of their older traditions.

Their area is divided into eight independent villages (pueblos), each village with its own traditional board. The division was made by catholic missionaries during the colonial period. The eight villages (Ocho Pueblos) are Loma de Bácum, Vícam, Pótam, Tórim, Belem, Rahúm, Huírivis and Cocorit.

In the early 1900s, during the end of the so-called Yaqui War, Yaquis were deported and forced to leave their homes. Some were deported to Yucatán, others to Tlaxcala, and some fled to northern regions, which today are part of the United States.

During the Yaqui War, the federal and state governments considered three possible solutions to the conflict with Yaquis: 1) a war of annihilation 2) deportation 3) colonization. Under President Porfirio Diaz, Yaquis were either executed, hanged, shot, or died on the battlefield. The war of annihilation waged against them was systematic and protracted; what would today be called genocide.

When Yaquis were forced into exile, they brought with them dress, musical instruments and other paraphernalia that were important for conducting traditional ceremonies in another place. In Tlaxcala, the men enlisted and were part of the first line of defense during the ongoing civil war.

The head of the Yaqui battalion and army was General Jose Amarillas. It was through his support that the now repatriated objects came to Sweden. He was a friend of the Danish sisters Bodil Christensen and Helga Larsen, both of whom had supported Yaquis on a number of occasions.

Throughout history, the Yaquis struggle has had four main purposes; defend the homeland, self-government, water supply and that those who were deported to different places could return. They have shown tremendous resilience and perseverance, largely due to highly valued cultural symbols of a shared identity. Their existence is about traditions not forgotten and the land as a living being, and these concepts have created a strong sense of cultural belonging.

"Last Friday we went to Toluca and got a collection of zarapes of the kind that the Indians themselves use. Early on Saturday, we set off for Tlaxcala with the Danes to attend a dance party with the Yaqui Indians. It was undeniably an absolutely sensational event. I can't in a few words portray the party, it would require several pages. However, it was the Indians in the Indianbooks, who celebrated a memorial feast for their dead. The dances went on for more than a day and a half.

The Yaqui soldiers, who normally walks around wearing sloppy and loosefitting European uniforms, had now dressed up wearing masks and ankle rattles and were performing half-naked their ancient pantomins with deer and coyotes. It was amazing but utterly fascinating. All strangers are forbidden at the dances but the Danes are good friends with the general and consequently we were able to move completely freely and film and photograph at will. We even managed to buy some of a dance attributes and later on we hope to get more. It is a collection, which most museums would envy us."

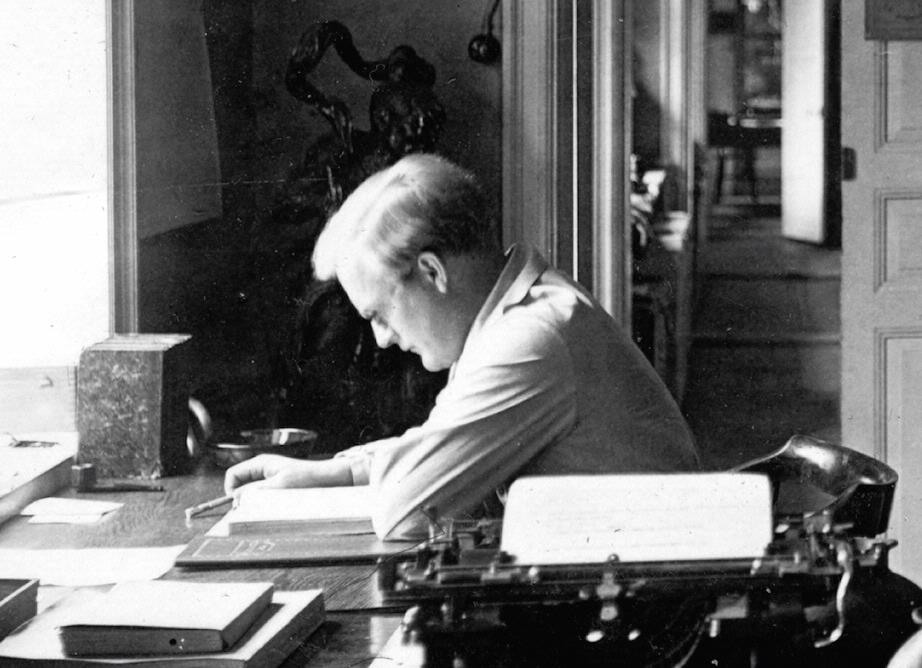

Archaeologist, ethnographer, professor and leader of the second Swedish Mexico expedition. Between 1954-1966 he was director of the National Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm, now the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm.

Archaeologist, ethnographer, curator at the National Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm, now the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm.

Lived in Mexico and participated in the work of the second Swedish Mexico expedition, with collecting of objects, documentation and photography.

Sister of Bodil Christensen, lived in Mexico and, like Bodil, participated in the second Swedish Mexico expedition with the collecting of objects and documentation.

The black and white photographs were taken by Bodil Christensen in 1934. In the photographs we see how the families who were accommodated in Tlaxcala attempted to recreate their traditional everyday life. Yaquis stayed in Tlaxcala between 1934 and 1940, and during this period lived in the architectural complex of the Franciscan monastery of Nuestra Señora de la Asumpción. The soldiers stayed with their regiment, while the women tried to live as close to the men as possible.

Yaquis carry out a lucto pajko a year after a person dies. In Tlaxcala, a ceremony was recreated that was largely identical to the ones performed in Sonora. The ceremony included pascolas, venado and matachines. From a photograph in the collection, we can see that coyotes also participated, but no sacred objects were collected from this ritual.

The photographs furthermore show how the ceremonies took place outdoors and not inside a temple, indicating that the rituals were not dedicated to a patron saint. A lucto pajko had to be performed under a roof of intertwined branches, but since these were not awailable in Tlaxcala, they instead used blankets to recreate what would be the representation of juya ania; an important concept in Yyaqui culture.

This is a world where both material and spiritual resources are safeguarded. Those who wish to gain the gift of dance and music, have to venture there through dreams, to confront demons and contact ancestors.

Produced in cooperation with: